8

Multisensory and Multimedia

Interviews with Hiroshi Ishii, Durrell Bishop, Joy Mountford, and Bill Gaver

Until recently, rendering bits into human-readable form has been restricted mostly to displays and keyboards—sensory deprived and physically limited. By contrast, “tangible bits” allow us to interact with them with our muscles as well as our minds and memory.

Nicholas Negroponte, a founder of MITrsquo;s Media Lab

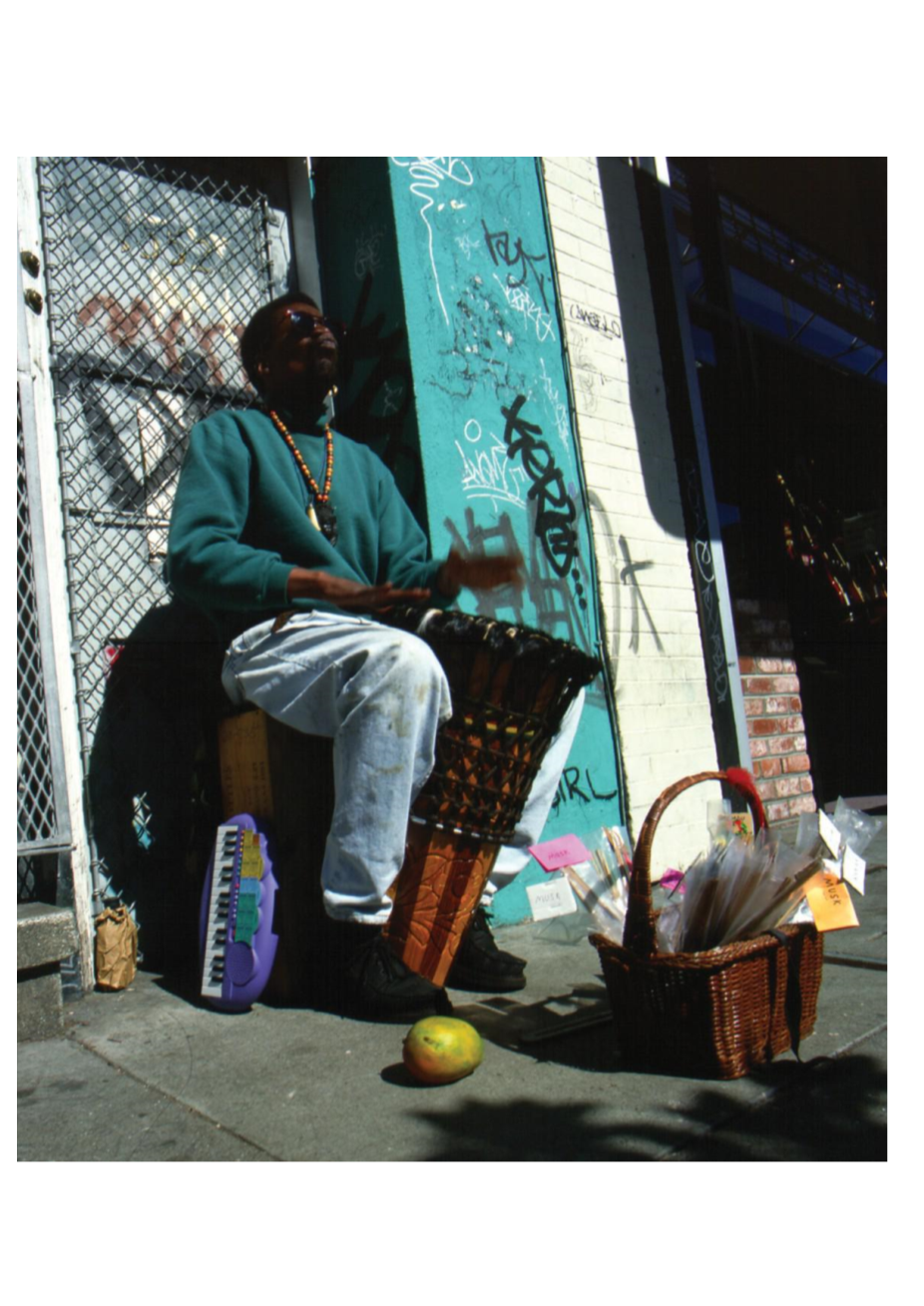

- The drummer surrounds himself with stimulants for all of the

senses, and an electronic keyboard (from Yamaha)

Photo

Steven Moeder and

Craig Syverson

We all have five senses; how sad that our connection to computers is “sensory deprived and physically limited,” as Nicholas Negroponte so aptly phrases it. Visual displays are gradually improving, but our sense of touch is limited for most of the time to the feel of the keyboard and mouse. Sound exists as a dimension in the interface but so far has not taken the prominent place that seems possible. Smell and taste are not yet present. And then, what about dimensionality? Can we go beyond x, y, and z, and make more use of the time dimension? Although we already have some examples of animation and time-based behaviors, we could go so much further, if we think about making full use of multiple media.

This chapter explores the opportunities for interaction design to become multisensory and to take advantage of multimedia.We start with a plea to break away from the status quo and design for better use of our vision and touch. Then we look at the work of some remarkable innovators. An interview with Hiroshi Ishii, professor of the Tangible Media Group at MIT Media Lab, introduces the concept of “tangible bits.” Durrell Bishop, an interaction designer based in London, talks of interfaces made up

of things that are physical and connected. Joy Mountford tells the story of pioneering the use of QuickTime, when she was Head of the Human Interface Group in Advanced Technology at Apple, and her research into audio at Interval. Bill Gaver, researcher and interaction design teacher, talks about designing sound, discusses the psychology of affordances, and shows some examples of concepts that have subtle psychological relationships with the people that use them.

Vision

“Visions of Japan” Exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 1991–92

-

- Room 1, Cosmos—”The Realm of Clicheacute;”

- Room 2, Chaos—”The Realm of Kitsch”

Why should you be chained to your computer? You sit for so many hours at a time, staring at that small rectangular display of information: it is always the same focal length, with no relief for the eyes; it makes no use of your peripheral vision; it is so dim that you have to control the surrounding lighting conditions to see it properly.Why not break away, and wander in smart environments covered in living displays, or carry a system with you as an extension of your senses, augmenting vision?

In 1991 there was a wonderful exhibition in London called “Visions of Japan,”1 based on a concept by the architect Arata Isozaki.You moved through three large spaces, each celebrating a theme. The first was “The Realm of Clicheacute;,” which presented various entertainments.There were examples from such arts as the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, incense connoisseurship, calligraphy, martial arts, and popular and classical performing arts, to sexual pleasures, and the traditions of the underworld.

The second space was “The Realm of Kitsch,” which examined the nature of competitiveness in games and sports. Competition is the basis of baseball, golf, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation singing contest, pastimes like pachinko, and the majority of other topics of daily conversations.

The third theme was “The Realm of Simulation,” and this space demonstrated a dramatic expansion of the potential for visual display. The entire floor and walls of a high-ceilinged

rectangular hall were completely covered with moving images. Some of the time they were separated into individual images making a collage of screens, and some of the time they were huge panoramas, stitched together to form a single image. One movie was recorded in the concourse of a mainline railway station in Tokyo at rush hour, so that as you moved through the space, you were part of a sea of Japanese commuters, hurrying in every direction to find their trains. The images on the ground were projected from the ceiling, so that the visitors to the space became part of the display screen, covered in moving images themselves, as they stood transfixed or moved slowly forward.

Here is a quote from Isozakirsquo;s description of this theme in the catalog:

Electronic devices of innumerable kinds have spread throughout society, transforming its systems and practices from within.

Television, video recording, pocket-size audio devices and giant video displays, compact computer devices, like television screen hookup game equipment and personal computers, are irreversibly altering our ways of life.

The images produced by these systems are displayed on screens but they are completely separated from the real things themselves— processed, edited, and otherwise qualitatively changed, often into something completely different. That process can be manipulated, creating impressions of convincing simulation.

The constant bombardment of such simulated images could cause those images to flow back into the real world, blurring the line between real and simulated. Perceptions may become completely reversed, producing the sensation that reality is only part of a world of simulation.

This idea of “blurring the line between real and simulated” was demonstrated very convincingly by the exhibition, but the audience were passive receivers of the experience, like cinema- goers; there were no interactive

剩余内容已隐藏,支付完成后下载完整资料

英语原文共 17 页,剩余内容已隐藏,支付完成后下载完整资料

资料编号:[138805],资料为PDF文档或Word文档,PDF文档可免费转换为Word